- Startup Chai

- Posts

- Quick Commerce Reckoning, Flipkart’s Exit, and Varun Alagh Doubles Down

Quick Commerce Reckoning, Flipkart’s Exit, and Varun Alagh Doubles Down

Plus fundraising news about Neeman’s

For years, India’s quick commerce story was sold as inevitability. Faster delivery would automatically mean bigger baskets, stronger loyalty, and eventually profits. Ten minutes became the headline. Convenience became the justification. Capital became the fuel. What no one wanted to confront early enough was the cost of keeping that illusion alive.

That reckoning has now arrived.

Quick commerce in India is no longer a growth story. It is a margin story. And margins, unlike GMV charts, don’t lie.

The sector has grown fast, no doubt. India’s quick commerce market crossed $6.5 billion in 2024 and is projected to hit $40 billion by 2030. Blinkit, Zepto, and Instamart have rewired urban grocery behaviour. Millions of Indians now default to apps for milk, bread, and last-minute groceries. But beneath that adoption sits an uncomfortable truth: every 10-minute promise is structurally expensive.

A typical quick commerce order in India still averages ₹450-₹500. The gross margin on groceries sits around 18-22%. From that, platforms must pay for dark store rent, inventory holding, shrinkage, delivery riders, surge incentives, and marketing. The last mile alone costs ₹35-₹50 per order. Add store operations and tech, and contribution margins remain wafer thin, often negative outside the top few hyper-dense clusters.

This is why the business model has changed tone.

Earlier, quick commerce apps sold speed. Today, they are selling discipline. Fewer discounts. Higher minimum order values. Platform fees. Surge pricing disguised as “rain fees” or “handling charges.” These aren’t experiments. They are survival tactics. Zomato’s own disclosures show Blinkit’s contribution margins improving only after pulling back discounts and tightening assortments. Zepto, despite doubling revenue to ₹4,454 crore in FY24, still posted losses of over ₹1,200 crore. Speed scaled. Profitability didn’t.

The deeper issue is that quick commerce was never designed for India’s price-sensitive consumer. The model works best when baskets are large, repeat frequency is high, and customers don’t flinch at service fees. That’s not India. Indian consumers optimise ruthlessly. They compare prices across apps. They abandon carts over ₹10 differences. They want instant delivery, but not instant markups.

That tension is now playing out in public.

Dark stores were meant to be invisible efficiency engines. Instead, they’ve become capital sinks. Each dark store costs ₹30-40 lakh annually to operate. Scale helps, but only in tightly packed neighbourhoods. Expansion into tier-2 cities looks good on pitch decks, but breaks economics fast. Demand thins out, rider utilisation drops, and fixed costs stay stubbornly high.

Globally, this isn’t new. In the US, GoPuff burned billions before slowing expansion and shutting underperforming micro-fulfilment centres. In Europe, Getir exited multiple markets after failing to justify unit economics. The pattern is consistent: quick commerce works only under very specific density and spending conditions. India doesn’t magically escape that math.

What’s different in India is the capital pressure. With IPO conversations now unavoidable, the tolerance for cash burn has collapsed. Public markets don’t reward GMV narratives. They reward cash flows. Every rupee of “growth” must explain how it eventually turns into profit. And that’s where quick commerce struggles.

This is why we’re seeing pivots that would’ve been unthinkable two years ago. Blinkit moving toward inventory-led control. Swiggy experimenting with physical Instamart stores to increase trust and basket sizes. Zepto dialing down expansion and talking openly about burn reduction. These aren’t signs of confidence. They’re signs of correction.

For consumers, this means fewer freebies and more fees. For founders, it means abandoning growth theatre. And for investors, it means admitting that 10 minutes was always a promise built on borrowed capital.

Quick commerce isn’t dying. But it is growing up. And growing up, in this business, is expensive.

Let’s go through what else is happening in Indian startup world. Grab your simmering cup of StartupChai.in and unwind with our hand-brewed memes.

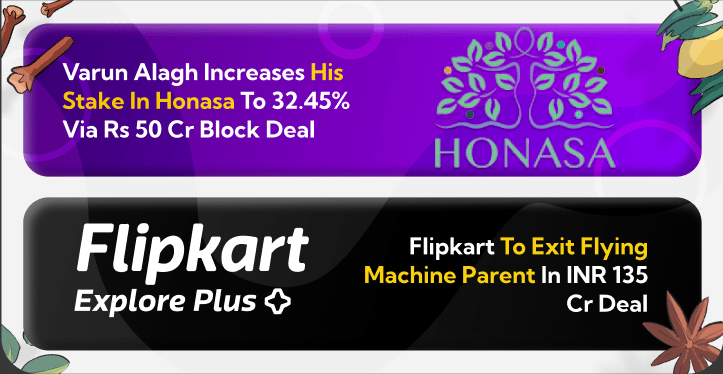

“Lo Mai Chali Banke Hawa”: Flipkart To Exit Flying Machine Parent In INR 135 Cr Deal

Flipkart is exiting Flying Machine’s parent in a ₹135 Cr deal, unwinding a minority investment it made in 2020 for ₹260 Cr.

Post-transaction, Flying Machine will become a wholly owned subsidiary of Arvind Fashion, closing the loop on brand ownership. The move aligns with Flipkart’s ongoing restructuring as it trims non-core bets ahead of an IPO.

Read more here

“Hum Honge Kamiyab Ek Din”: Varun Alagh increases his stake in Honasa to 32.45% via Rs 50 Cr block deal

Varun Alagh has increased his stake in Honasa Consumer, picking up ₹50 Cr worth of shares through a block deal on December 29.

The purchase of 18.5 lakh shares at ₹270 apiece takes his personal holding to 32.45 percent, or 10.56 crore shares. The move quietly reinforces promoter confidence, with the overall promoter group stake now rising to 35.54 percent in the Mamaearth parent.

Read more here

Sustainable footwear brand Neeman’s has raised fresh capital from a mix of new and existing investors as part of its ongoing Series B round that began in June 2022. The company issued 54,915 Series B2 CCPS at ₹6,465 per share to raise ₹35.5 Cr, according to its regulatory filings.

Read more here

How did today's serving of StartupChai fare on your taste buds? |